|

|

MAY 8, 2025 |

|

|

|

In the Fentanyl Era, Compassion Without Enforcement Costs Lives |

|

|

- Spokane Regional Stabilization Center allows people in crisis to avoid jail in lieu of treatment for their mental health or substance abuse issues. |

|

Spokane is now living the tragic consequences of a hard truth: when public safety and community standards are no longer enforced, disaster follows.

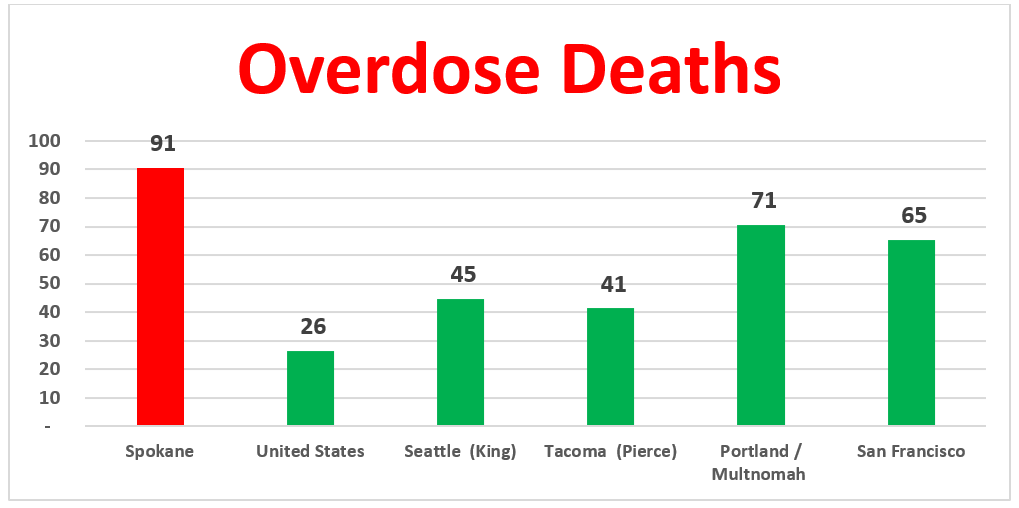

Our overdose death rate now far surpasses that of larger West Coast cities—including Seattle, Tacoma, Portland, and San Francisco—which, until recently, were grappling with much higher numbers. In 2024, Spokane recorded a 39% surge in overdose deaths, claiming 352 lives. This year, we are on track for another 40% increase—potentially exceeding 500 deaths. |

|

|

|

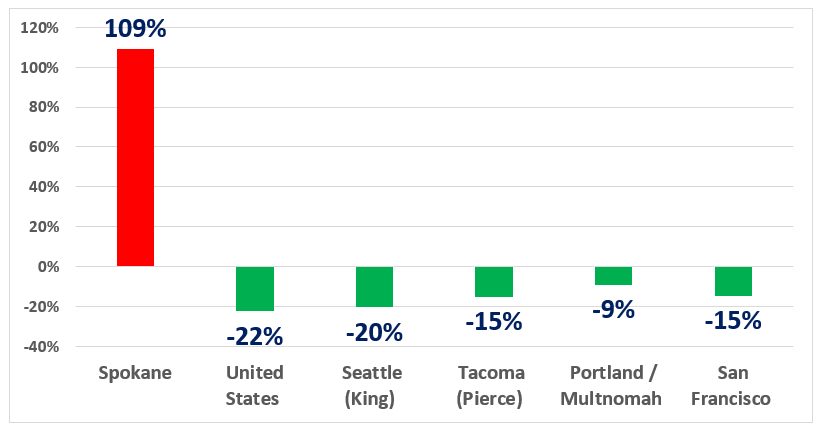

Just two years ago, Spokane’s overdose rate was substantially lower than those of the same West Coast cities. Today, the opposite is true—while overdose deaths have declined across all of them, Spokane’s overdose death rate has skyrocketed by 109%. |

Overdose Deaths:

|

|

|

The lessons from these dramatic changes are straightforward: where the U.S. and other cities have embraced a shift toward constructive enforcement paired with treatment options, Spokane continues to double down on non-engagement policies—the same approach that helped drive the nation’s overdose crisis in the first place.

What’s now clear across the country—and confirmed by both liberal and conservative experts alike—is that in the fentanyl era, ignoring enforcement does not spare people harm. It simply leaves them to die. Unlike alcohol or older drugs like heroin, fentanyl and methamphetamine completely rob individuals of the capacity to seek treatment voluntarily. The result is that older policies promoting a wait for “readiness” are no longer compassionate or effective.

This thinking is echoed by addiction experts, who increasingly warn that today’s synthetic drugs are not like those of the past. They destroy decision-making, damage the brain through repeated overdoses, and trap users in a cycle few escape without direct intervention. That’s why successful cities are reimagining enforcement—not as punishment, but as a gateway to recovery.

Consider Denver and Portland—cities once committed solely to harm reduction. Today, their leaders are pairing accountability with treatment. Legal leverage is used not to punish, but to connect people with life-saving services, including Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) and long-term recovery programs.

Spokane’s continued policy missteps are also eroding basic safety and stability. As seen in Portland, when downtown areas are perceived as unsafe, people stop coming. Businesses close. Jobs vanish. And with them go the tax revenues needed to fund housing, treatment, police, and other essential services. This is how a city falls into what urban analysts call a "doom loop": public disorder drives economic decline, which in turn diminishes the resources needed to fix it. (Consider that even with Portland’s recent policy reversals, 2,600 downtown businesses have closed, and its office vacancy rate stands at 34.7%—the highest in the nation.) --As the City’s CFO for 17 years, I can tell you that Spokane is closer to that edge than many realize.

So, Spokane faces a stark choice:

Continue the status quo of non-enforcement and watch both overdose deaths and public disorder spiral out of control—driving business closures and community collapse—or follow the lead of cities learning from hard experience: using enforcement as a lever to guide people toward treatment, while protecting public spaces and public safety.

With leadership and will, Spokane can still reverse course—before more lives are lost and further damage is done to the fabric of our community. |

|

|

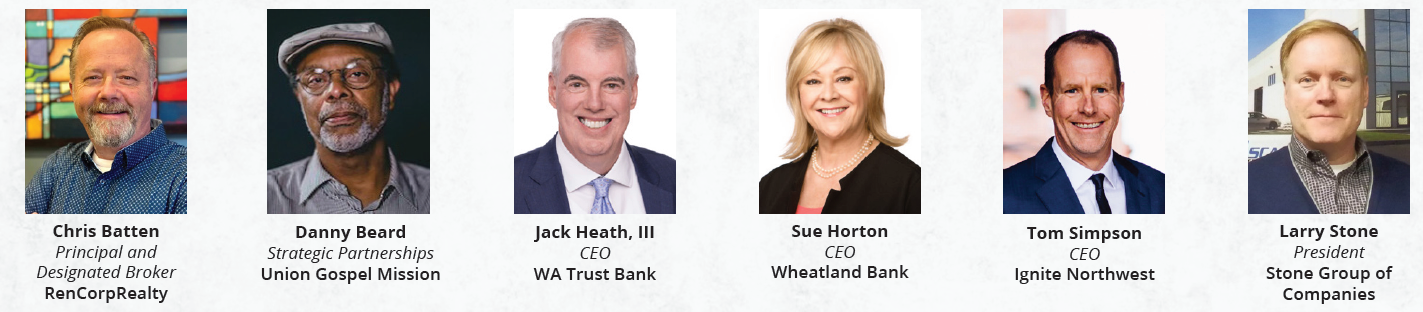

LEADERSHIP |

|

|

|

|

ACCESS TO ADVOCACY |

|

|

|

DIAMOND LEVEL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PLATINUM LEVEL |

|

|

|

GOLD LEVEL |

|

Bank of America | CPM Development Corporation | Diamond Parking Services Goodale & Barbieri Co | Hainsworth Laundry Company | Linden Street Solutions Lukins & Annis Attorneys | Lydig Construction | Mackin & Little NAI Black/Black Realty Management | RenCorp Realty | Spokane Hardware Supply STCU | SVN Cornerstone |

SILVER LEVEL |

|

Alliant Insurance Services | Anthony's Restaurants | BECU Bouten Construction Co | Budinger & Associates Inc CliftonLarsonAllen LLP | CollinsWoerman | DCI Engineers | Merit Electric of Spokane | Randall & Hurley Tom Simpson | Umpqua Bank | Walker Construction Inc |

BRONZE LEVEL |

|

Able Label | AllStar Glass | Arby's of Spokane | Associated Industries of the Inland Northwest Baker Construction | Banner Bank | Bernardo Wills | Breakthrough Inc | Coffman Engineers Commercial Construction & Improvements | Copenhaver Construction |DeVries Business Services Dupree Building Specialties | Empire Bolt & Screw | Finley Construction | GoJoe Patrol | GT Capital Integrus Architecture | Kiemle Hagood | Marsh & McLennan Agency | MJM Grand Inc NW Granite | Pella Inland Northwest Peppertree Hospitality Group | Perlo Construction Selkirk Development |Spokane Regional Plan Center | Stifel Financial | Summit Electric Surface Experts Franchising | The General Store | Thomas Hammer Coffee Roasters Trudeau's Marina | Vandervert Developments | West Plains Development |

|

|

|

BOARD OF DIRECTORS |

|

|

|